Along the Belt and Road—Breaking the Cycle of Underdevelopment in Latin America

January 28, 2022

About the author:

Carlos Martinez, Independent Political Affairs Commentator

The last few months have seen a significant expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative in Latin America and the Caribbean. Although this region of the world is not the most obvious fit for an undertaking that was originally modeled on the Silk Road—a network of trade routes linking East Asia with the Middle East, Africa, and Europe—the reality is that the countries of South America, Central America, and the Caribbean share many of the same needs as their counterparts in Central Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Most Latin American countries won their formal independence from Spanish and Portuguese colonialism in the 19th century, but they found themselves in the shadow of an incipient North American imperialism. The Monroe Doctrine, first articulated by President James Monroe in 1823, denounced European colonialism and interference in the Western Hemisphere, not on the basis of anti-colonial principle but with a view to buttressing US hegemonic designs. Since that time, the U.S. has tended to consider Latin America as its “backyard”—a collection of countries subjected to the control (direct or indirect) of Washington.[1]

Eduardo Galeano wrote that the transition from colonialism to neocolonialism made little difference to Latin America’s position within the global capitalist economy. “Everything from the discovery until our times has always been transmuted into European—or later, United States—capital, and as such has accumulated on distant centers of power. Everything: the soil, its fruits and its mineral-rich depths, the people and their capacity to work and to consume, natural resources, and human resources.”[2]

Galeano’s words were written almost 50 years ago, but they still ring true. The U.S. continues with its hegemonic strategy in relation to Latin America, a strategy which seeks to make the region’s land, natural resources, labor and markets subservient to the needs of US monopoly capital. The U.S. has shown a consistent interest in Mexican labor, in Chilean copper, in Brazilian land; but it has been indifferent to the needs of the people of these countries to development, to a decent standard of living, to social justice. And when the U.S. fails to get what it wants through quiet pressure and economic coercion, it does not hesitate to use force, for example supporting coups against the elected governments of Bolivia[3] and Venezuela,[4] or imposing illegal sanctions on Nicaragua[5] and Cuba.[6]

As a result, Latin America continues to suffer significant underdevelopment in many areas. The emergence of China as a major investor and trading partner is therefore proving to be indispensable for the region’s economic progress.

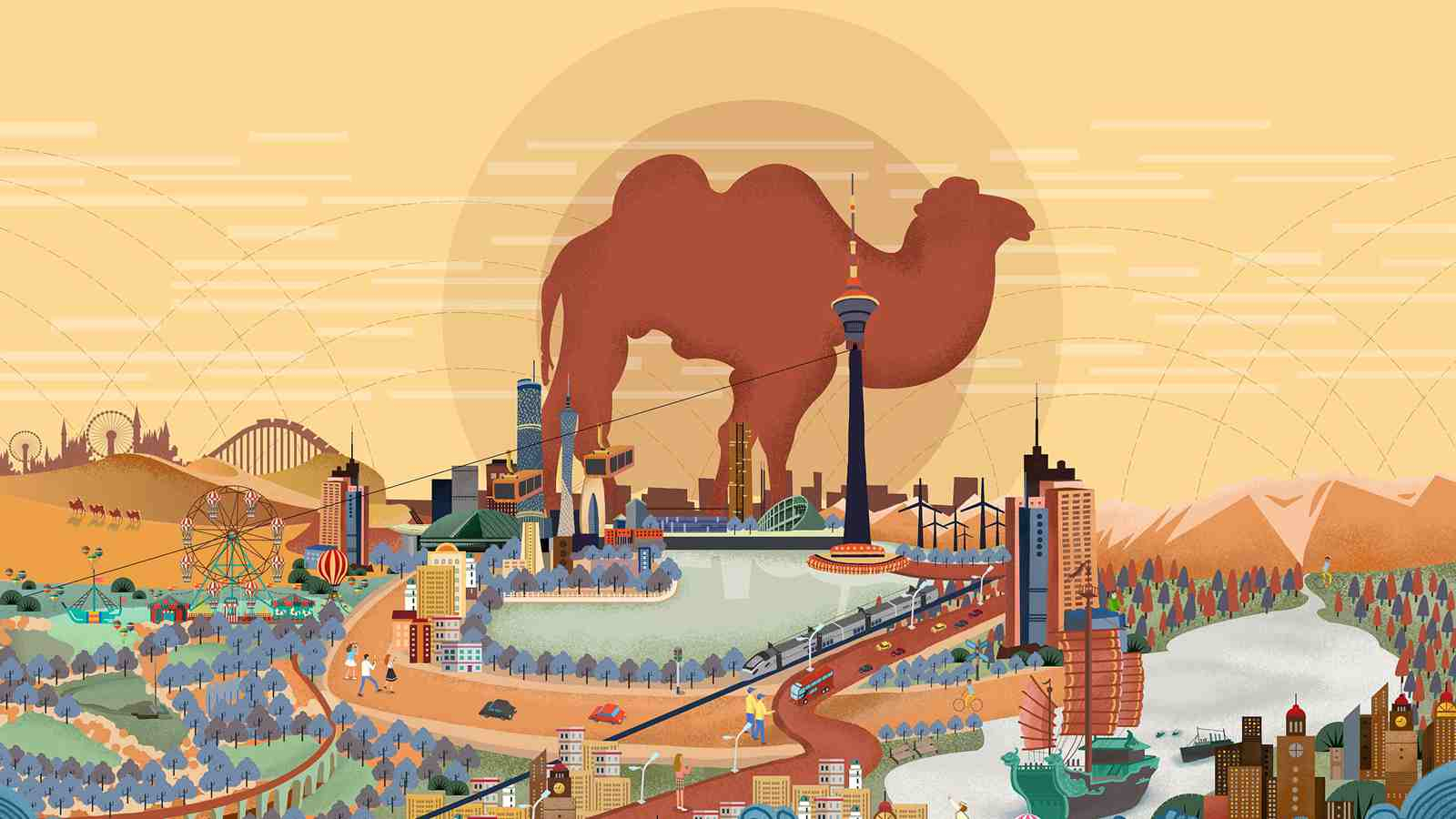

(Source: video.cgtn.com)

Steadily Increasing Economic Ties Between China and Latin America

In the last two decades, economic links between Latin America and the People’s Republic of China have been expanding at a dizzying rate. Bilateral trade in 2000 was just $12 billion (one percent of Latin America’s total trade); now it stands at $315 billion.[7] In the same time period, China’s foreign direct investment in Latin America has increased by a factor of five.[8]

Since the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, 21 of the 33 countries in the Latin American and Caribbean region have signed up to the China-led global infrastructure development strategy. Infrastructure projects have been a particular focus for Chinese firms. Writing in Foreign Policy in 2018, Max Nathanson observed that “Latin American governments have long lamented their countries’ patchy infrastructure.” China has “stepped in with a solution: roughly $150 billion loaned to Latin American countries since 2005.”[9]

Chinese investment has been widely recognized across the region for its positive economic and social impact, particularly in terms of facilitating government projects to reduce poverty and inequality. Kevin Gallagher, in his important book The China Triangle, writes that “Venezuela has been actively spending public funds to expand social inclusion to the country’s poor. The country… was able to fund such expenditures given the high price of oil in the 2000s—and due to the joint fund with China.”[10]

A similar story can be told about transformative social programs in Bolivia, in Brazil (under the Workers Party governments led by Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff) and elsewhere. Brazil under the Lula and Dilma governments (2002-2016) won global acclaim for its unprecedented campaigns to tackle poverty, homelessness, malnutrition, and lack of access to education and healthcare. As part of its rejection of the Washington Consensus and its embrace of multipolarity and South-South cooperation, Lula’s administration massively expanded economic ties with China. Then foreign minister Celso Amorim said the Brazil-China relationship formed part of a “reconfiguration of the world’s commercial and diplomatic geography.”[11]

Chinese investment has proven particularly attractive to those governments in the region that seek to protect their sovereignty and improve the living standards of their populations. Investment from the international financial institutions (most notably the IMF) has typically come with punishing conditions of privatization, deregulation, and fiscal austerity. China’s development loans, on the other hand, come with no such strings attached. Gallagher affirms that Chinese banks “do not impose policy conditionalities of any kind, in keeping with general foreign policy of nonintervention.”

Support During the Pandemic

Aside from trade and investment, China gives over $5 billion in aid to Latin America each year. Since the start of the pandemic, China has provided around half the region’s COVID-19 vaccine doses, [12] with a number of countries including Chile, El Salvador, Brazil, and Uruguay relying almost exclusively on Chinese vaccines.[13] Indeed, as early as July 2020, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced a one-billion-dollar loan to support vaccine access in Latin America.[14]

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has spoken of his gratitude for Chinese support with vaccines, testing kits, ventilators, and personal protective equipment, “We’re very grateful to China, to the Chinese government, to the President of China…We asked him for support with medical equipment, and a huge number of flights with medical equipment have arrived from China.”[15]

Cuba Joins the Belt and Road Energy Partnership

Cuba and China established diplomatic relations in 1960, just a year after the Cuban Revolution. However, the relationship was complicated by the emerging Sino-Soviet split, and the two sides had little to do with one another in the 70s and 80s. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, compounded by a deepening blockade by the U.S., Cuba faced an unprecedented economic crisis. China’s economy, on the other hand, was starting to take off, and it stepped in to provide Cuba with urgently-needed investment, trade, and aid, starting with the supply of a million bicycles.[16]

In 1993, awarding former President Jiang Zemin the Order of Jose Martí, Cuban President Fidel Castro spoke passionately about the successes of Chinese socialism: “Only socialism could have been capable of the miracle of feeding; clothing; providing with footwear, jobs, education, and healthcare; raising life expectancy to 70; and providing decorous shelter for more than one billion human beings in a minute portion of the planet’s arable land.”[17]

Since the early 1990s, bilateral trade has grown steadily, and China now accounts for around 30 percent of Cuban imports and exports.[18] China invests heavily in telecommunications, mining, and energy in Cuba, and Chinese consumer goods are very popular on the island. Cuba exports sugar, nickel, and other goods to China.

Most recently, Cuba has joined the Belt and Road Energy Partnership, a Chinese-led program designed to strengthen coordination around energy investments and promote clean energy. David Castrillon, Research Professor in international relations at the Externado University of Colombia, observes that “Cuba, like so many other countries in the Global South, faces both the basic needs of the population for access to electricity, as well as the global demands to transition to more sustainable energy sources. It is in this context that cooperation with a country like China is so important, as China not only has the experience and expertise in developing these high-quality sustainable energies, but also the willingness to work hand in hand with other countries.”[19]

With limited natural resources and suffering under a US economic blockade that has persisted for over 60 years, Cuba has benefited tremendously from its deepening win-win relationship with China. As Chinese President Xi Jinping said when visiting Havana in 2014, China and Cuba are both socialist countries, and the common ideal, beliefs, and objectives have tightly united the two peoples together. The two should be “good friends, good comrades, and good brothers forever.”[20]

China and Nicaragua Resume Diplomatic Ties

On December 9, 2021, Nicaragua’s Foreign Minister Denis Moncada announced the resumption of diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Nicaragua. As Wang Wenbin, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson, noted, “The two governing parties and two countries share revolutionary friendship and brotherly bonds.”[21]

There is enormous scope for the two countries to advance economic cooperation, particularly in infrastructure construction and renewable energy. Following the announcement of bilateral relations, the two sides signed several cooperation agreements, including a memorandum of understanding on cooperation under the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the 21st Century Maritime Cooperation.[22]

Speaking at the official reopening of China’s embassy in Nicaragua, Moncada stated, “We are sure that we will continue working together, strengthening each day the fraternal ties of friendship, cooperation, investment, expanding communication channels with the Belt and Road, strengthening peace, stability, security, development, and progress for the mutual benefit of our peoples and humanity.”[23]

Nicaragua is another country that has suffered terribly as a result of US intervention, destabilization, and sanctions. Increasing coordination with China will certainly help it to break out of underdevelopment and solve the needs of its people.

A Rising Tide of Multipolarity

With the expansion of Chinese investment and trade, Latin America has the historic opportunity to break out of its status as a “backyard” of the U.S. to climb the ladder of development and to affirm its status as a key player in an increasingly multipolar world. Kevin Gallagher has noted that Latin American governments no longer consider it necessary to submit to the neoliberal Washington Consensus or to endure US domination “in large part because they believe they have an alternative in China.”[24] The late Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez considered that an alliance with China constituted a “Great Wall against American hegemonism.”[25]

In stark contrast to the U.S., China treats other countries on the basis of equality and works to develop mutually beneficial relationships. Since Chinese loans don’t come with punishing conditions of austerity and privatization, Latin American governments have been able to leverage China’s investment and purchase of primary commodities to spend at an unprecedented rate on reducing poverty and inequality. As such, from Chile to Bolivia to Venezuela to Mexico, the relationship is producing tangible benefits for ordinary people in the region.

[2] Eduardo Galeano. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1997), pp. 190.

[10] Kevin Gallagher. The China Triangle: Latin America’s China Boom and the Fate of the Washington Consensus (New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press, 2016), pp. 85.

[11] Hal. Brands. Dilemmas of Brazilian Grand Strategy (United Kingdom: Lulu.com, 2012), pp.12.

[17] F. Castro, Castro Presents Jose Marti Order to Jiang Zemin, Fidel Castro Speech Database, accessed Jan. 21, 2022. https://australianmuseum.net.au/chinese-scroll-painting-h533

[24] Gallagher, op cit, pp. 233

This article is from the January issue of TI Observer (TIO), which is a monthly publication devoted to bringing China and the rest of the world closer together by facilitating mutual understanding and promoting exchanges of views. If you are interested in knowing more about the January issue, please click here:

——————————————

ON TIMES WE FOCUS.

Should you have any questions, please contact us at public@taiheglobal.org