Thorsten Jelinek, Senior Fellow, Taihe Institute; Director, Taihe Institute Europe Center; Associate Director, the World Economic Forum (2011-2014)

Learning from the history of telecommunications

The telecommunications industry has become one of the primary targets of the heightened demand for digital sovereignty, epitomizing the fierce competition over technology leadership as well as the crisis in global governance. The problem is not one of sovereignty or the right to make independent policy choices, but the fine line separating sovereignty from nationalism and protectionism. Once relegated in the West as a commodity and low-profit-margin industry, mobile communications networks are now regarded as key enabler for the digital transformation, as critical infrastructure, and thus a matter of economic and national security.

Since the Trump administration and continuing under the Biden administration, the United States has started banning 5G network equipment from Chinese suppliers and kept pushing the European Union, its members, and other leading economies to exclude and remove Huawei and ZTE equipment from their mobile network infrastructure. This ban is complemented by the US government’s unilateral trade restrictions on China’s semiconductor makers and importers to sabotage and contain China’s development in this and other key technology areas that are deemed a security risk. Those measures are aligned under the Biden administration’s whole-of-government approach, which seeks both to strengthen US competitiveness and to restrict and contain the development of China.

(Souce: www.reuters.com)

For now, the European Union has resisted an outright ban of Chinese technology companies. However, the European Commission has introduced a series of cybersecurity regulations that also target Chinese technology companies. While cybersecurity is essential for mitigating the rapidly changing and intensifying landscape of cybersecurity threats and for building trust and confidence in the digital economy, the EU aims at minimizing its exposure to “high-risk suppliers” and “avoiding dependency” on these suppliers at national and EU levels. Although no evidence has been provided about intentional security breaches linked to Chinese network equipment, and bans based on the nationality of the equipment provider offers little assurance for cybersecurity, several European countries have effectively sanctioned Chinese telecommunications equipment.

After a few decades of open trade and global innovation in telecommunications, during which Western mobile operators enjoyed buying China’s lower priced and increasingly high-quality mobile communications equipment, the rise of protectionism and technology nationalism in the West reminds of the technological silos that determined most of the 20th century, especially in the telecommunications sector.

During the previous century, a few Western states – including the United States, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, as well as Japan – could sustain their own “natural monopolies” as well as their domination of the international telecommunications industry. This system of regulated telecommunications monopolies lasted in the U.S. from 1913 to the 1980s and in Europe until the 1990s. It was sustained through rent-seeking, cartelistic arrangements, and government favoritism on a national level and reinforced through the technology hegemony of the West and its domination and control at the international level. While less developed countries could set up their own state monopolies and benefit from Western technologies, the West gained most from its monopoly, as it kept its international advantage through domination and coercion, as well as control over technology standards, adoption, spillovers, and its multinational corporations governing global supply chains.

Such asymmetrical distribution of power and technology was also sustained on a multilateral level, mainly through the Western-dominated International Telecommunication Union (ITU), which effectively suppressed the less developed world in the acquisition of knowledge for developing their own native technology industry. Controlling the international policy discourse, the West did not set up ITU for bargaining or the redistribution of technological capabilities, and an asymmetrical settlement for joined services for the benefit of less-developed countries remained a voluntary matter for rich world operators. Overall, the West was not interested in the non-West to become technologically self-sufficient.

Amongst the late emerging economies, however, China has been the only exception who successfully managed to break through the Western hegemony and become a global leader in mobile communications. Harvard Professor Dani Rodrik has shown that market mechanisms alone are not sufficient to transform a poor country into a rich one, which has always been the laudable purpose of Western development aid. However, this transition from poor to rich requires state intervention, including the development of human capital, robust institutions, and modern industries. China’s development approach confirms Dani Rodrik’s observations. However, as the West has lost its relative competitiveness in telecommunications, it no longer tolerates what it had practiced itself during most of the 20thcentury, that is state interventionism.

China’s rise

Similar to other less developed or late emerging economies, China’s telecommunications network was lagging behind those of Western nations. In 1978, China operated merely 1.93 million telephones. Thus, as part of the reform and opening-up agenda in 1978, the Chinese government started viewing telecommunications as a critical infrastructure for economic development and competitiveness.

To catch up with the West and narrow the technology gap between China and the West, the government pursued three development paths. First, in the early 1980s, the government initiated a national initiative to boost domestic R&D. The purpose of the government-led program was to track global trends and carry out research in areas useful for China; to train China’s new generation of students, scientists, and engineers and generate up-to-date industry and scientific knowledge; and to offer R&D funds for the state-owned and growing private enterprise sector. These R&D objectives were part of a larger plan, which was in support of the development of China’s national defense system. China’s national R&D program resembled the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) in the United States, Eureka in Western Europe, or the Human Frontier program in Japan.

Second, China started importing Western technologies using loans from the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank. The import of the latest Western technologies gained momentum in 1986, when the State Council approved lower import tariffs. Importing Western technology was a clear break with the previous socialist doctrine of self-reliance. However, to prevent foreign-dependency and build local capacity, China followed the “policy of import, digestion, absorption and creation.” The Western companies selling their products to China were required to transfer their technologies to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Western companies were required to form joint ventures (JVs) with local firms, as practiced in other industries, and to set up their production and assembly lines in China. The JV approach was necessary to upgrade China’s outdated production facilities.

The potentially huge telecommunications market provided bargaining power for the Chinese government, so Western companies mostly complied. While Siemens and its rival Alcatel were the first transnational corporations (TNCs) in China, companies like Cisco, NEC, Lucent, Nortel, or Ericsson soon followed suit as they feared losing this market entry opportunity. As a result of the JV-driven foreign direct investment approach, imports decreased, local manufacturing outputs increased, and Western companies retained their high market share for some time.

The third critical path of China’s catching-up was the government’s gradual introduction of a market for local equipment manufacturers. The challenge was the recurring technology gap that emerged with each generational advancement. Domestic competition between equipment manufacturers intended to accelerate the catch-up process and narrow the gap with each technology upgrade.

The government actively encouraged the establishment of local companies, supported independent innovation, and eventually fostered their internationalization. A group of three enterprises emerged in the mid-end 1980s, including ZTE (1985), Julong (1989), and Huawei (1987). Datang was another company that was established in 1998. While the former two and Datang were SOEs, Huawei was the only private company. Those four local companies fiercely competed against each other and against foreign companies. While the SOEs could strongly rely on government support and state loans, Huawei faced a continuous uphill battle as it largely lacked government support.

The introduction of competition paid off. The Chinese manufacturers built cheaper yet reliable alternatives and shortened the catch-up cycles between each new generation of communications technology. Consequently, foreign companies were increasingly pushed out of the market and towards the end of the 1990s, many JVs often ended in divorce.

In 1996, the import policy from 1986 had ended. While core network components were no longer imported, unavailable technology continued to be licensed from Western companies like Qualcomm’s CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access) technology or Cisco’s data switches and routers. With technology adoption and spillovers predominantly under the control of the Western multinationals, Chinese equipment manufacturers were accused of imitating or reverse engineering Western production and assembly lines or even intellectual property (IP) theft. In any case, the success of catching up is attributed to the combination of three development approaches – national R&D program, import and joint ventures, domestic competition – all of which led to the technology capacity and capability necessary to ensure the establishment of a fast-growing domestic telecommunications and ICT (Information and Communications Technology) industry.

The introduction of market competition proved to be a determinant of China’s success. Unlike the other two SOEs, ZTE was state-owned but privately managed and, therefore, did not have to be accountable under different ministries. Among other factors, ZTE’s success could be largely attributed to this aspect of enhanced self-management and thus the ability to respond more quickly to market demands. This explains why Huawei, which is the only privately-owned company amongst the four domestic competitors, came out as the winner of the local competition.

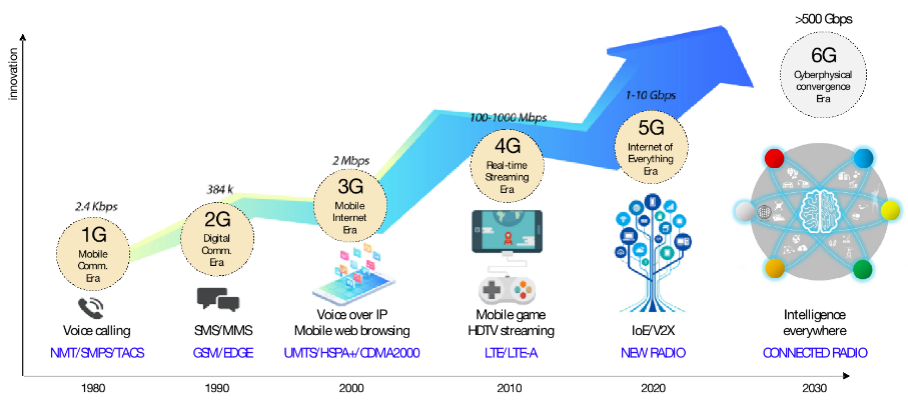

Around 2005, Julong was driven out of the market and Datang remained a local player. Despite its domestic and international success, ZTE increasingly lagged behind Huawei during the 2000s. Over the next generations of mobile communications technology, including 3G (2000), 4G (2010), and 5G (since 2020), Huawei subsequently became the global industry leader in terms of global market share, technology standards-setting, as well as declared 5G and ICT patent families. Huawei is ahead of its main competitors, including Samsung (Korea), ZTE (China), LG (Korea), Nokia (Finland), Ericsson (Sweden), or Qualcomm (the United States), and owned 40 percent of all 6G patents worldwide as of September 2021.

Overall, the rise of China’s telecommunications industry was extremely successful. In 1978, only 0.38 percent of China’s households had a telephone, which meant that China lagged behind the United States by 75 years. In 2004, China started ranking first globally in the total number of both mobile phone (270 million) and fixed line (260 million) users, and, in 2008, in total Internet users (253 million). In October 2021, about 1.64 billion mobile phone subscriptions were registered in China, and the number of Internet users had surpassed one billion as of June 2021, thereby further reducing its digital divide.

China’s successful development approach has confirmed Rodrik’s observation that market forces alone are insufficient to achieve structural change. The government played an important role in setting up the domestic playing field, formed the industry actors and defined the rules of the game. In 2019, however, Huawei and other Chinese high-technology companies got severely hit by unilateral sanctions imposed by the United States, which had the effect of damaging not just Huawei’s but China’s development. The Western world is suppressing China’s international rollout of 5G networks, and there is a complete decoupling of R&D work leading to the sixth generation (6G).

Conclusion

Ubiquitous digitalization and connectivity will increase the threat surface for cyberattacks, which poses a national security issue. However, the history of telecommunications suggests that today’s tension between the West and China is less an issue of security, but more one of competition and domination. While China’s state interventionism will continue for China to reach its development goals and further transition towards a prosperous economy and society, the West experiences its own renaissance of state intervention to tackle climate change and manage its own transition towards a fully digitalized future. This could be good news, as the negotiation of new competition rules is less difficult than negotiating national security concerns.

The history of telecommunications also confirms that telecommunications is an infrastructure that is primarily critical for development and growth rather than for sustaining national security. As no other technology, mobile communications has been the most successful one, and the most successful mobile network generations were those defined by standards that became globally implemented. Decoupling is justified on the basis of national security risks while undoing the previous success and regressing to old technological and ideological silos of the West.