About the author:

Cheng-Chwee Kuik; Professor, Universiti Kebangsaan (National Universtiy of) Malaysia (UKM); Non-Resident Fellow, The Foreign Policy Institute, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University

Paul Evans, HSBC Chair in Asian Research, University of British Columbia; Pok Rafeah Chair, Institute of Malaysian and International Studies (IKMAS), UKM

The devastation resulting from the ongoing war in Ukraine continues to spread. Coming on the heels of the COVID pandemic and a downward spiral in U.S.-China relations, the conflict is a human tragedy. It has thrown into stark relief existing geo-political tensions, the variance in national responses, and different visions of security structures for an era of radical uncertainty.

Russia’s blatant invasion and the brutality of the conflict are unquestionable. What surprises is the variation in responses. The unity in NATO and among US allies has taken form in a chorus of condemnation, massive military, diplomatic and economic support for the Zelensky government, and a series of sanctions against Russia.

(Source: www.ft.com)

Yet governments in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, while usually expressing alarm and abhorrence, have been far less willing to participate in the sanctions or support the Western narrative on the causes of the war.

Far more so than at the outbreak of the Cold War in the mid-20th century, the list is lengthy of countries unpersuaded by the US and European calls to arms and strengthened alliances or for framing this as a battle between democracy and autocracy. Despite sharp differences, neither India nor China is lining up with the West. Most others in the developing world along with a sizeable list of middle-income countries aren’t either.

This time round, The Rest matter a great deal more in terms of population, economic weight, and diplomatic capability.

The members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) are emblematic of the new forces in play and the actions of regional states that must make choices but deplore being forced to choose. Their key ideas and responses - pledging and pursuing “non-alignment” by actively practicing inclusive, impartial “multi-alignment” - deserve careful attention.

Diverse in political systems, level of economic development, languages, religions, and histories, they have an institutional bond in ASEAN built upon norms and practices that have special value in an era of great power rivalries and turbulence. Committed to globalization, principles of comprehensive and cooperative security, and the virtues of inclusive multilateral processes, they are a useful vantage point on the Ukraine crisis and navigating an unstable security order.

ASEAN Reactions

ASEAN’s ten members have responded to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in diverse and often contradictory ways. Singapore condemned and imposed sanctions on Russia; Myanmar’s military junta endorsed the Kremlin’s actions; Indonesia condemned the violation of sovereignty but without mentioning Russia by name and without implementing sanctions. In March, all ASEAN states except Laos and Vietnam voted at the UN General Assembly to deplore Russia’s aggression. In April, six ASEAN members abstained from voting to suspend Russia from the UN Human Rights Council, while Laos and Vietnam opposed the resolution, and the Philippines and the Myanmar government-in-exile supported it.

The regional commonalities are instructive. Nearly all have avoided siding with any power, emphasized their “neutrality, and positioned to keep options open.” Indonesia, the host of the upcoming G20 Summit in Bali, has resisted pressure from Western countries to exclude Russia from the meeting, instead, inviting both presidents Putin and Zelensky. Singapore, despite being the only ASEAN state condemning the invasion and imposing unilateral sanctions on Russia, opted to abstain from the Human Rights Council vote. Voices region-wide decry “double standards” in the West’s neglect of earlier conflicts and refugee crises elsewhere.

The ASEAN reactions to the war are not fundamentally because of feelings of hypocrisy or the view that it is a distant European conflict, not its own. At root is an abiding prudence about offsetting risks and avoiding being pulled into a permanent alignment with any major power. It is systemic risks that are of the greatest concern to security and stability and regional cohesion in a neighborhood that was long a battleground of external imperial powers.

Historical memory matters. As smaller actors suffered from centuries-long Western colonialism and decades-long Cold War politics, Southeast Asian countries see the present-day U.S.-Russia and U.S.-China rivalries as more a matter of big-power competition than an issue of ideological contestation. The fight in Ukraine is chiefly a proxy war between the major powers.

The Russia-Ukraine War is unfolding as U.S.-China rivalry is intensifying on multiple fronts. There is alarm about potential polarization and the erosion of ASEAN centrality in mitigating tensions in the broader Asia-Pacific world. There is apprehension about the expanding Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad) cooperation, as well as the announcement of AUKUS (Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States) security agreement in September 2021. And there is resistance to defining the strategic setting as a grand competition between democracies and autocracies with a guiding principle of cooperation among the idea of “like-minded” defined on the basis of regime type.

Alliances or Alignments?

ASEAN states see eye-to-eye with the West about the crucial importance of upholding national sovereignty and territorial integrity. But they do not think collective-defense alliances and exclusive alignments are the solutions.

In Europe, Finland and Sweden’s bids to join NATO signify that alliance now trumps neutrality as the path to smaller-state survival. These decisions are driven by two factors - the threat from Russia is becoming more profound and direct, and support from a U.S.-led NATO is immediately available, credible, and reliable.

In Southeast Asia, the sources of threats are less-than-clear-cut, and allied support, less-than-certain. China has been a source of growing security concern, especially to those Southeast Asian claimants and littoral states in the South China Sea, increasingly worried by Beijing’s growing maritime assertiveness. At the same time, however, China is a huge regional presence and indispensable economic and diplomatic partner for Southeast Asian governments generally occupied with tackling more pressing domestic challenges and non-traditional security problems in post-COVID-19 economy and society.

Part of the strategic logic is the danger of a self-fulfilling prophecy: actively and overtly forming an exclusive alignment targeting a perceived China threat will turn a security concern into an immediate and greater threat. Action-reaction countermeasures will provoke China to act more aggressively.

Hence, while ASEAN states are deeply concerned about the dangerous precedent set by Russia, they have generally avoided joining the West in taking a united and strong position against Moscow.

This combines with a resistance to full alignment with the United States. America’s Indo-Pacific strategy, while welcome, is widely seen as focusing too heavily on military and defense issues and insufficiently on development and functional cooperation, giving uneven attention to all ASEAN members, and hobbled by uncertainty about domestic instability and the prospect of more policy reversals to come, the shadow of Trump.

ASEAN states, hence, have been pledging “non-alignment” as seen in Vietnam’s “Four No’s” policy in its 2019 Defense White Paper, and Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto’s emphasis on “non-alignment” at this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue. This pledge, however, has gone hand-in-hand with an actual practice of “multilayered alignments,” where virtually all ASEAN states pursue a complex blend of cooperative arrangements with multiple partners in areas of defense, diplomacy, and development.

This practice has deepened and widened in recent years, in large part driven by growing big-power tensions externally and elite political needs internally. Region-wide ruling elites rely heavily on development-based performance legitimacy to govern. This motivates them to pursue as many concrete, productive partnerships across key domains with as many key powers as possible.

Non-Alignment and Neutralism: Then and Now

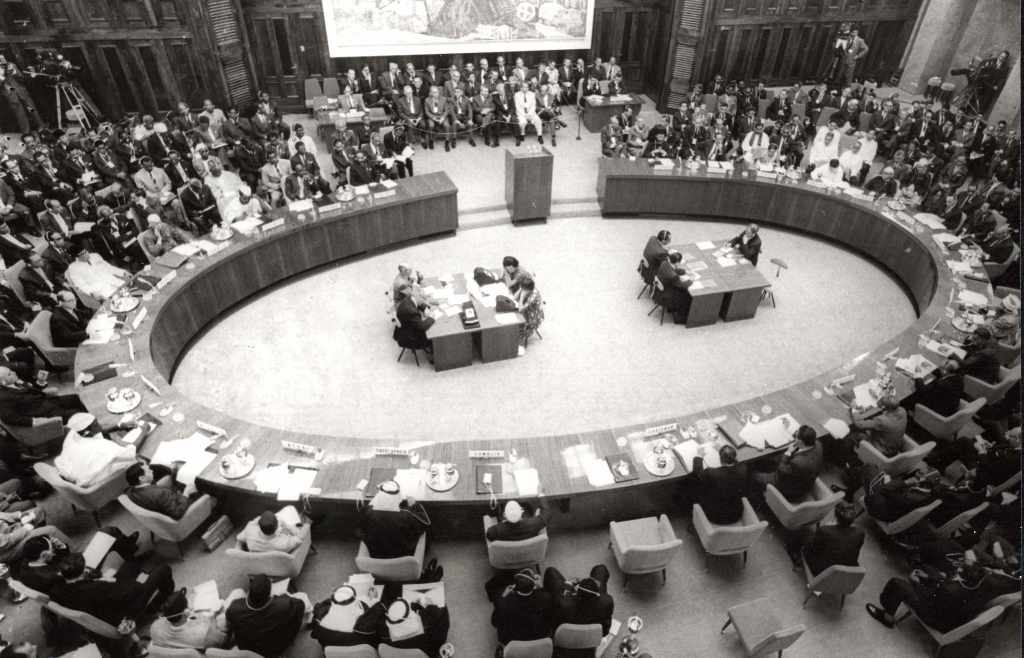

“Neutrality” was a core foundation, if contested, when ASEAN issued the declaration of The Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) in 1971. Then debates centered on distinctions between “neutrality” (non-involvement by a state in a war between other states) and “neutralization” (the way in which neutrality is attained) in legal terms and mainly in wartime situations. “Neutralism” was framed as the peacetime foreign policy approach of a state, either alone or in concert with others. Adopted by many newly independent states, neutralism was often associated with impartiality and non-alignment with the blocs led by either the United States or the Soviet Union. “Non-alignment,” in turn, was equated with “non-alliance” during much of the Cold War period.

In the early 1990s, several states in formal alliances joined the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Thailand and the Philippines, the two treaty allies of the United States in Southeast Asia, joined NAM in 1993, following the footsteps of other Southeast Asian states. The terms “non-alliance” and “non-alignment” were no longer co-terminus. Here, “non-alignment” is used to refer to membership in NAM or the declared principle of impartiality vis-à-vis the competing powers, whereas “non-alliance” to a decision of not joining formal alliances (i.e., military cooperation between sovereign states that entails mutual defense commitment).

(Source: en.wikipedia.org)

Alignment in today’s Southeast Asia is more flexible, multifaceted, supported by institutionalized consultative processes, and sustained by continuous dialogue and policy coordination, both bilaterally and multilaterally, including such ASEAN-led mechanisms as the ASEAN Regional Forum, the ASEAN Plus Three, the East Asia Summit, and the ADMM+ (ASEAN Defense Ministers’ Meeting) process.

To align, in its simplest terms, means to come together, to work with each other, to link oneself to larger collective efforts of coordinating actions and pursuing common aims. It is more than a dialogue or routine interaction. It involves coordinated actions and concerted efforts for a continuous harmonization of wider ends.

Alignments are different from alliances that entail a mutual defense commitment, a bond with a single great-power patron, and often a targeted source of threat. Alignments allow room for simultaneous and selective cooperation with multiple partners and even with both competing powers. This applies for those not in any formal alliances but also for treaty allies. Thailand forged strategic alignment with China in the late 1970s that have been revived in recent decades. The Philippines has an alliance with the United States as the cornerstone of its external policy while developing defense cooperation with China and expanding its strategic ties with Australia, Japan, and India.

Other original members of ASEAN have maintained longstanding and robust defense and security partnerships with outside powers. Malaysia and Singapore continue to commit to the Five Power Defense Arrangements involving the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand. Singapore’s alignment with the United States is the most robust security partnership between an ASEAN state and an outside power.

As the U.S.-China rivalry intensifies and uncertainty grows, more ASEAN states have developed additional layers of alignment with a wider range of countries. Indonesia and Malaysia, both critical of AUKUS, have quietly pursued strategic diversification. Malaysia has entered into more defense MoUs than ever before (including an upcoming one with the United States). Indonesia has launched 2+2 mechanisms with several Western and Asian powers while broadening its long-held defense partnership with the United States. Vietnam has pursued similar multilayered partnerships with various outside powers, developing defense ties and cultivating multi-domain cooperation, mainly bilaterally.

Co-eval is the expansion of cooperative ties with China that go well beyond trade and investment. Virtually all are partners in BRI-related infrastructure and connectivity-building ventures. Many conduct military exercises and buy arms from China. And several do joint river patrols with China.

For now, ASEAN’s inclusive multilayered alignments are more about mitigating and offsetting multiple risks than counter-balancing any specific threat. Hedging against risks amid uncertainty, the greater the uncertainty, the greater the scope and scale of alignments.

Where Active Non-Alignment Meets Inclusive Multi-Alignment

The idea of “Active Non-Alignment” being developed by Latin American thought leaders resonates with the outlook and practices of ASEAN states’ resistance to lining up unequivocally with either the United States or China, valuing deepened relations with both, wary of formalized alliances along the lines of NATO, and interested in maintaining an open global trading system in the face of calls for economic decoupling and new forms of protectionism.

For Middle Powers in the West like Canada, Australia and New Zealand which favor multilateral institutions (inclusive and selective), which champion “universal” values including freedom, democracy, human rights and the rule of law, and which have deep security and economic ties with the United States, non-alignment and neutrality are non-starters.

But as the balance of power continues to shift, as most of the developing world steadily moves toward strategic recalibrations, and as fears of a two-bloc world and intensifying U.S.-China rivalry deepen, both ASEAN-style approaches and Latin American thinking need fresh attention.

Both are about avoiding speculation on the future big-power relations and avoiding antagonism with either side. Both are about actively creating layers of collaboration, cultivating channels of communication, and keeping bridges of respectful coexistence open for all even when the space for maneuver is shrinking.

Strategic positioning is dynamic. An escalation of the conflict in Europe, a direct U.S.-China military clash, or Putin-style territorial aggression in Asia, could alter thinking quickly. But for the moment, Southeast Asia’s multilayered-alignments through bilateral efforts and the web of ASEAN-centered arrangements are the functioning foundations for regional peace and prosperity.

Please note: The above contents only represent the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views or positions of Taihe Institute.

This article is from the June issue of TI Observer (TIO), which is a monthly publication devoted to bringing China and the rest of the world closer together by facilitating mutual understanding and promoting exchanges of views. If you are interested in knowing more about the June issue, please click here:

http://www.taiheinstitute.org/Content/2022/06-30/1115477342.html

——————————————

ON TIMES WE FOCUS.

Should you have any questions, please contact us at public@taiheglobal.org