About the author:

Brian Wong Yueshun, Ph.D. candidate, Oxford University; TI Youth Observer

In 1961, when the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was first founded in the then Yugoslavia, the loosely defined alliance of states came together in an attempt to push back against a bifurcated and polarized global order. With the Warsaw Pact on one hand, and NATO on the other, the Cold War came to define the primary bulwark and mantle of the NAM’s objectives - for states to collectively resist being incorporated into blocs under Soviet or American-European influence, and for them to work together in advancing an ideologically neutral and practically tenable vision of world peace.

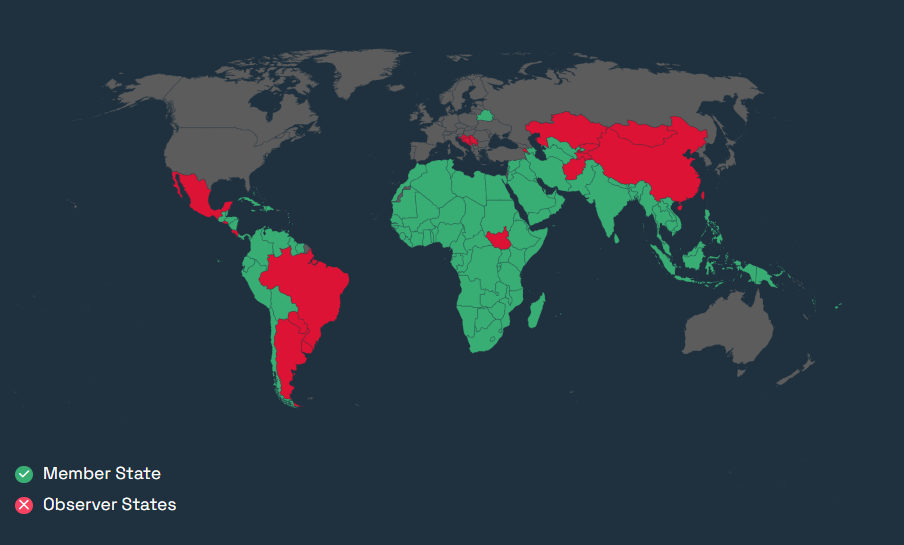

(Source: www.nti.org)

The Shifting Contexts Underpinning the Non-Aligned Movement

While the powers of small and medium states were fundamentally circumscribed by their far more powerful neighbors, the NAM successfully demonstrated, for the three decades of its interactions with the Cold War, that when smaller non-aligned actors came together to repel pressures for them to take up arms, sides, and ideologically doctrinaire positions, they too, came to cultivate significant political capital. For instance, states with vast populations such as India (under Jawaharlal Nehru) and Yugoslavia (under Josip Tito) pushed back against the pressures from both the Warsaw Pact and NATO to align on proxy and regional conflicts.1 For Yugoslavia, the split with the Soviet Union, amidst Cold War tensions, allowed it to carve out a distinctive zone of relative neutrality in the Balkans. Both Nehru and Egyptian President Nasser advocated for “peace” to be achieved through “working for collective security on a world scale and by expanding the region of freedom.”2 Thus, the 1956 Declaration of Brijuni came to be a defining hallmark of the NAM countries’ collective foreign policy – to coordinate, seek, and negotiate an uneasy, yet much-needed peace, amongst their members, large or small.

In the sixty years following the Declaration of Brijuni, the Cold War concluded in 1989 with the crumbling of the Berlin Wall, which brought an end to the ideological Iron Curtain – or so many had thought – dividing the West from the Soviet Union and its remnants. Even in the aftermath of the outbreak of the military conflict in Ukraine, attempts to draw parallels between the geopolitics of the Cold War and that of today remain overwhelmingly futile. The world is not in a Cold War: for one, there exist multiple poles of competing and collaborating geopolitical interests, and there are more than two clearly equipped powers with divergent yet overlapping worldviews. The extent of economic and financial interdependence between states – notwithstanding the imposition of sanctions by large powers on one another – remains significant and incomparably greater than thirty years ago. Globalization has brought the peoples and civil societies of states closer and facilitated the confluence and synergy in ideologies and values across historically conflictual countries.

The underlying commitments of the NAM remain relevant today. They were the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, encapsulated by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and articulated in a 1954 speech in Sri Lanka by Nehru, which addressed Sino-Indian relations: mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference in domestic affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence.3

Such aspirational values are not only worth pushing forward, but are also very much antidotes to the state of global polarization and divisions of today. Yet, precisely because today’s context is so radically different, there must be reforms and adaptations to such principles - in favor of what I shall introduce shortly – as a renewed manifesto for non-alignment.

Toward a New Ethos of Non-Alignment

Historically, non-alignment had been a pivotal principle ensuring that small and medium powers steered clear of large-scale conflicts as much as possible; additionally, the underscoring of equality and mutual benefit, as positive objectives underpinning international collaboration, had been translated into members of the NAM’s developing economic and trade agreements that exclusively favored one another. This was achievable, in the sense that neither the USSR nor the proverbial West saw it as necessary, or fostered further action to ensure the integration of energy and commodity provision, supply chains, and financial systems.

Today, further integration is clearly no longer feasible. As globalization brought national economies – even those in apparently distinct geopolitical blocs – substantially closer. Furthermore, many small and medium powers have shifted from taciturn, defensively neutral positions towards engaging in all sorts of proactive geopolitical strategies, such as hedging or cultivating utility for multiple larger powers. Consider, for instance, the past decade of diplomacy from ASEAN states, which saw them balance their ongoing military and strategic ties with America, with their rapidly growing economic and financial stake in China – this offers a powerful example of what hedging looks like. Or, indeed, take a look at Kazakhstan and Qatar’s emergence as sites for conversations and negotiations over the fate of Afghanistan: both are prime exemplars of how small and medium-sized countries can make themselves useful and relevant in broader international political contexts.4 Non-alignment is no longer about non-involvement, but about proactive neutrality: countries do their very best to remain fundamentally neutral, yet this need not manifest through, and often requires the express abandonment of, inaction and passivity.

More generally, with technological, civil society-based human-to-human, and economic-financial exchanges becoming vastly more ubiquitous and contiguous across countries, the prospects for non-aligned states to sever relations entirely, or to minimize their exposure to exogenous shocks, have decreased markedly. For example, the fates of countries in the Horn of Africa are increasingly intertwined with the future of NATO and [perceived] credibility of its members to honor their words over counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. Thus, it is high time to reflect, once again, upon what non-alignment has historically both meant and entailed.

The Case for a New Non-Alignment Manifesto

To design a new manifesto for non-aligned states today, the core set of principles should reflect a set of prerequisite commitments and values that accommodate the diverse range of viewpoints and interests that constitute the NAM. The following recommendations respond to those design requirements.

The first tenet is the decoupling of the interests of non-centered states from the narrowly defined, exclusionary interests of the great powers. By great powers, I refer to powers that possess strategic autonomy and the capacity to exercise such autonomy across a wide range of domains, including the political, economic, and financial; by exclusionary interests, I speak of interests that exclude or stand in stark juxtaposition to the interests of others. As an example of exclusionary interest, consider the United States as a great power, and its interests in staking claims in the South China Sea against the wishes of smaller states in the region and international protocols.5

Non-alignment does not imply having a stance, but the stance must be arrived at by appealing to the interests of small and medium independent states, as opposed to great power politics. Non-aligned states can say “No!” when cajoled and pressed by leading parties to take sides in international conflicts. Where they to partially align themselves over specific issues with great powers, the alignment would be innately transient and grounded in the interests of the non-aligned community as a whole. As such, the leaders of small states who opt to act as leaders of vassals for greater powers would be disqualified from any claim to non-alignment.

The second tenet is the renewed involvement of non-aligned states in multilateral institutions. Historically, the NAM had been equated with the pursuit of peace through informal arrangements and dialogue sandwiched between the Warsaw Pact and NATO. In a post-Cold War global order, one in which transnational institutions have come to increasing prominence, non-aligned states can and should make use of their access to multilateral institutions. They can collectively sway votes in the United Nations General Assembly, hold to account members of the Security Council, and empower and give a platform for voices that may otherwise be excluded from international discourse.

Multilateralism is a necessary ingredient in any cogent vision of pacifism. Historically, the NAM’s appeal for South-South cooperation had eschewedthe development of substantial entrenched connections and partnerships between non-aligned states in the Global South and North.6 However, peacekeeping, through both democratic dissemination and peace-oriented discourse, requires countries to do more than acting unilaterally or alignment within regional blocs. The war in Ukraine threatens to once again divide the world into two or more disparate coalitions. The non-aligned states must promote negotiations and transparent communication between adversarial powers to restore the global public’s confidence in international organizations such as the United Nations and the World Health Organization.

The most important and final commitment underpinning non-alignment is that no non-aligned state should ever approach international relations and statecraft through the normatively laden and values-centric lenses that major powers cultivate and propagate. Whether it be Russia’s revanchist Eurasianism7 or America’s fixation over the ostensible promotion of “democracy,”8 non-aligned states must do better than to be ensnared and turned into pawns echoing ideologies generated to justify hegemony and dominance.

To paraphrase Karl Marx, non-aligned peoples of the world, unite!

1. Dhiraj Kumar, “Ukraine Crisis: Nehru’s Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Doctrine Beckons India,” Times of India Blog, March 4, 2022, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/thedhirajkumar-com/ukraine-crisis-nehrus-non-aligned-movement-nam-doctrine-beckons-india/.

2. Ki-moon Ban, “Remarks to the High-Level Segment of the 16th Non-Aligned Movement Summit,” United Nation, August 30, 2012, https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2012-08-30/remarks-high-level-segment-16th-non-aligned-movement-summit.

3. “‘Non-Alignment’ Was Coined by Nehru in 1954,” The Times of India, September 18, 2006, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/non-alignment-was-coined-by-nehru-in-1954/articleshow/2000656.cms.

4. “Afghanistan Peace Process,” United States Institute of Peace, https://www.usip.org/programs/afghanistan-peace-process.

5. Council on Foreign Relations, “Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea,” Global Conflict Tracker, May 4, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/territorial-disputes-south-china-sea.

6. “What Is ‘South-South Cooperation’ and Why Does It Matter?,” United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, March 20, 2019, https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/intergovernmental-coordination/south-south-cooperation-2019.html.

7. Sarah Klump, “Russian Eurasianism: An Ideology of Empire,” Wilson Center, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/russian-eurasianism-ideology-empire.

8. “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson’s Statement on the ‘Summit for Democracy’ Held by the United States,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of People’s Republic of China, December 11, 2021,https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw665399/s2510665401/2535665405/202112/t2021121110466939.html.

Please note: The above contents only represent the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views or positions of Taihe Institute.

This article is from the June issue of TI Observer (TIO), which is a monthly publication devoted to bringing China and the rest of the world closer together by facilitating mutual understanding and promoting exchanges of views. If you are interested in knowing more about the June issue, please click here:

http://www.taiheinstitute.org/Content/2022/06-30/1115477342.html

——————————————

ON TIMES WE FOCUS.

Should you have any questions, please contact us at public@taiheglobal.org