About the author:

Gulshan Bibi, Ph.D. candidate, School of International Relations and Public Affairs, Fudan University; TI Youth Observer

Presenting non-alignment as a state policy, Mr. Kwame Nkrumah, the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, once said, “We neither face East nor West, we face forward.” In opposition to external pressure and alignments formed at the end of World War II, the concept of non-alignment surfaced and evolved during the Cold War. By encouraging the struggle against imperialism, colonialism, foreign occupation, and non-interference, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) supported self-determination, national independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity. It also propagated restructuring of the international economic system and aimed at international cooperation on an equal footing.

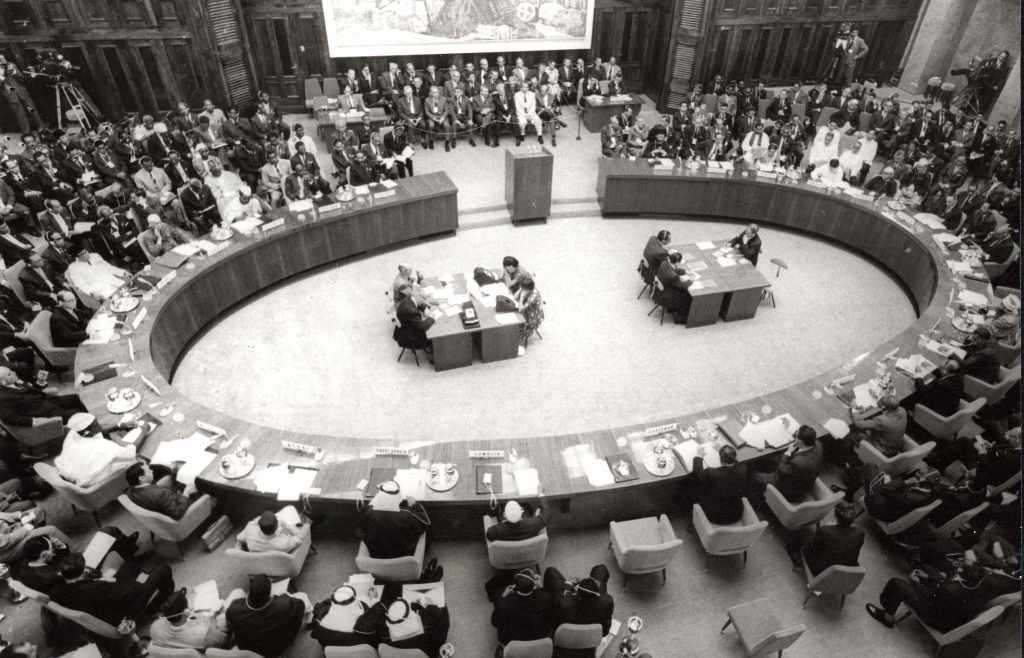

(Source: en.wikipedia.org)

At that time, the Western world viewed the NAM concept with negativity and believed that it was a pro-Soviet strategy. Later, with the end of the Cold War in 1991, the West considered that the concept of non-alignment had lost both relevance and substance. However, reports of the demise of NAM were premature. Many states chose not to join the united fronts that emerged as new power centers attempted to restructure the world into several blocs. Bloc restructuring, led by the U.S., occurred once again both before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. While the Russian military action in Ukraine has attracted Western condemnation and sanctions, for a majority of UN members, non-alignment with the U.S.-led bloc has been their stated position. The question arises as to why states are welcoming non-alignment? Such states hold that each country can operate an independent policy based on the coexistence of states and non-alignment. Moreover, an emerging new feature in this landscape is developing states embracing non-alignment status, not just over the Ukraine crisis, but more broadly as a principle of International Relations (IR). For many of these states, past colonialism was a key unifying factor. The current confrontation between the U.S. and Russia has spillover effects for many of these countries, causing them to believe they are merely buffer zones in the expansion of superpower’s spheres of influence. Thus, non-alignment is conceived as an essential element of their national interest, independence and survival.

Challenges and Prospects

While non-alignment as a strategy has influenced international thinking and approaches to many regional and global issues, it faces multiple challenges. There is a school of thought in the West which believes that non-alignment is an instrument for malign powers to legitimize their actions and should, therefore, be discontinued. In this view, non-alignment could be undermined quickly, because its existence was merely a product of, and justified by, Cold War rivalry; thus, without a cold war, non-alignment was neither justified nor necessary.

However, the existing state of affairs has demonstrated to many observers that the challenges to non-alignment are few, while the prospects are many. These prospects have convinced more states to revitalize non-alignment as a middle path in global competition. The proponents of non-alignment have understood that while the Cold War was not permanent, superpower rivalry will persist. Unlike many Western political leaders, Eastern thinkers believe that non-alignment remains relevant and must be continued. They frame their arguments on the following three bases:

1. There are still unresolved and new issues that require collective action. Moreover, many issues have taken new form and shape. Climate change, trade wars, revolution in military affairs, terrorism, ethnic conflicts, and gender-based violence are some of the common issues facing many states today. Furthermore, despite total elimination of colonialism, the essence of colonialism, such as control and hegemony exerted by external forces, continues in different forms. Neo-colonialism has evolved into a major concern of weak societies in the Global South. Foreign actors and their interventions do not and cannot resolve the aforementioned issues for developing and under-developed states. These issues are more adroitly handled and resolved through internal mechanisms and both bilateral and multilateral collaboration amongst states. Thus, non-alignment will and must continue to focus on these issues.

2. Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union (EU) - Brexit - is a pertinent example of how the current international system and institutions favor strong and resourceful independent states. Many other European states, however, have been unwilling to reduce their overrepresentation in international multilateral institutions. Since a number of states in the Eastern region are either small or weak, they find it difficult to compete with powerful states in the North. In order to safeguard their independence and protect national interest, they require support of either powerful states or a regional organization. Many of these states are a part of regional organizations like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and so on and so forth. For these states, which prefer partnership over aid, non-alignment could provide a strong base to advance their national and common interests.

3. Both national interest and priorities-based assessments underpin a state’s active engagement in international politics. Since the international system is dynamic and constantly changing, non-alignment helps states operate with more confidence and independence within the international arena. In the conduct of its IR, each state is committed to gaining support for its domestic priorities, seeking the peaceful resolution of conflicts and promoting economic development through regional and international cooperation. For many states, cooperation and multilateralism are seen as fundamental pillars in the realization of foreign policy priorities and advancement of development agendas. These states believe that the West has little to offer, or that offers of assistance are tainted with the legacy of colonialism. As a matter of principle, free nations oppose territorial expansion by force. They believe the world to be far more dangerous if big countries can invade peaceful neighboring countries with impunity. For the big powers, the Non-Aligned Movement remains unjustified today for the same reasons it was seen as unjustified during the Cold War. Yet, the proven path toward wealth creation and freedom is undercut by the developed world’s progressive development assistance paradigm, which rewards poor economic policies with more aid. In this view, aid is often laden with social agendas incompatible with the recipients’ cultural norms and directs investments toward politically favored industries, such as renewables, that reward elites and leave the poor poorer.

The concept of non-alignment is not only beneficial for small or weak states, but also assists more powerful states to promote their national interests. The unipolar system that emerged at the end of the Cold War was believed by many observers to underpin the international structure for the long run.

However, the “end of history” proved vulnerable as two major trends emerged: (a) a significant decline in US influence, and; (b) the emergence of new states with the power and capacity to influence the system. While there is still potential for global bloc politics to re-emerge, due to the expansion of the U.S.-led NATO military alliance system, the Eastern states are striving to build new economic coalitions. These Eastern states still require institutional support to effectively operate within an international order that is dominated by powerful Western interests. On that account, one cannot simply rule out the possibility of another round of major power rivalry in future.

Such a future scenario could force the majority of the states into yet another security dilemma similar to that of the Cold War era. The repeat of such a dilemma would force many states into decisions of whether to align, or not, with one or other of the extant power centers. Rather than attempting to reinvent the wheel, these states would prefer a role in global affairs independent of the strategic competition between the West and the East. However, the notion of non-alignment risks being narrowly defined as non-cooperation with the West or other present and future power centers, thus positioning non-aligned states as merely protesters. As such, NAM members must be willing to work with the West and other centers of power on the basis of constructive engagement. While cooperation-based development for nations that are free, secure and prosperous is crucial, achieving the objective of constructive engagement requires a focus on selective collaboration. From the perspective of non-alignment, a selective collaboration approach has the potential to facilitate better foreign policy and developmental outcomes.

Conclusion

Non-alignment represents both the desire and the means by which states may avoid emerging conflicts and reject participation in the creation of alliances that attempt to formalize the post-crisis division of the world. Adherence to non-alignment is prompted not only by the lack of affinity for the causes of post-crisis division, but also by the determination to maximize freedom of behavior in IR. Since the dynamics of the new world order are constantly changing, the international system may evolve into several rival blocs or power centers. In the face of the challenges posed by superpower rivalry and the new Cold War, non-alignment continues to offer an alternate policy response. Accordingly, non-alignment is not only a guiding principle, but also a strategy to ensure independence from both the present Western alliance system and power-centers that may arise in the future. The culture, values, concerns, and operational approaches of many states differ substantially from those practiced in the West. For the majority of countries that believe “freedom is the absence of external interference,” the current state of global affairs only strengthens the logic of non-alignment.

Please note: The above contents only represent the views of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views or positions of Taihe Institute.

This article is from the June issue of TI Observer (TIO), which is a monthly publication devoted to bringing China and the rest of the world closer together by facilitating mutual understanding and promoting exchanges of views. If you are interested in knowing more about the June issue, please click here:

http://www.taiheinstitute.org/Content/2022/06-30/1115477342.html

——————————————

ON TIMES WE FOCUS.

Should you have any questions, please contact us at public@taiheglobal.org